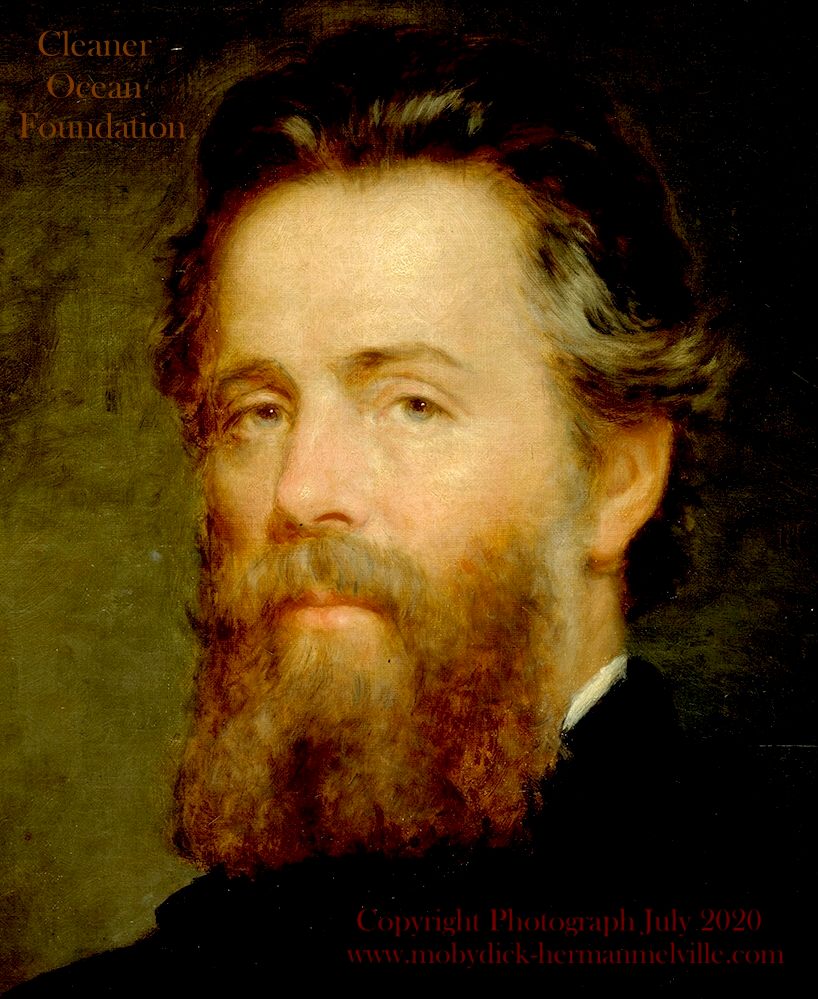

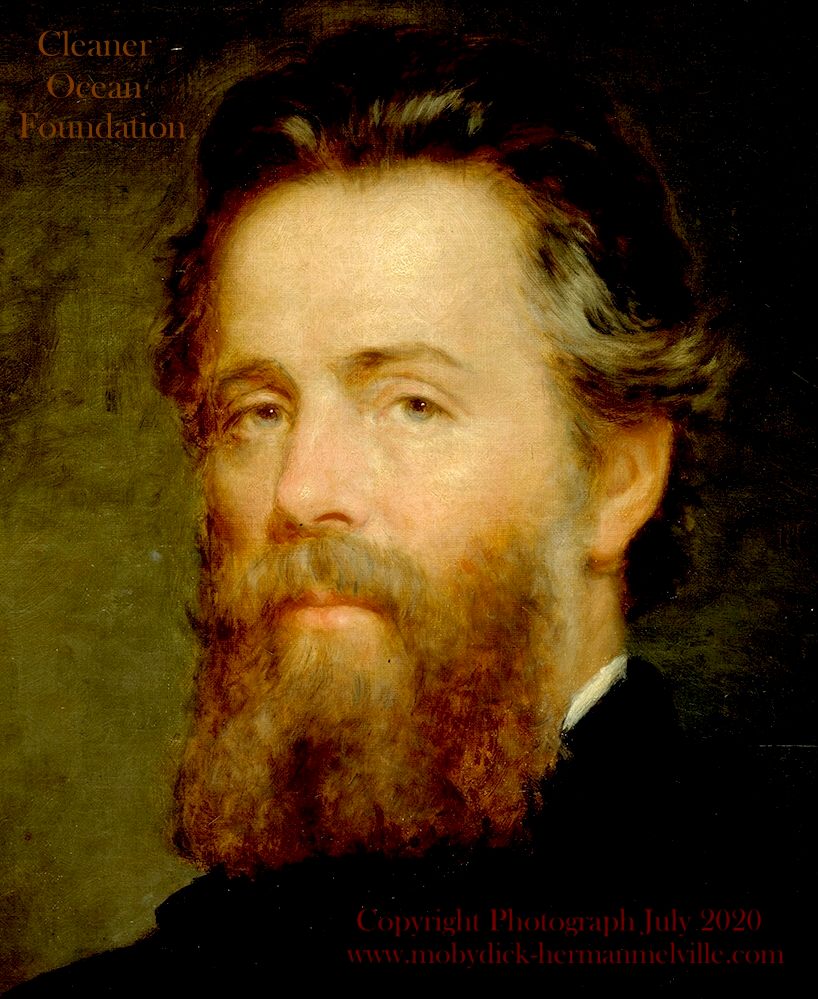

Portrait

of Nathaniel Hawthorne in oils

Hawthorne and his family moved to a small red farmhouse near Lenox, Massachusetts, at the end of March 1850.

It was while living here that he became friends with Herman

Melville beginning on August 5, 1850, when the authors met at a picnic hosted by a mutual friend.

Melville had just read Hawthorne's short story collection Mosses from an Old Manse, and his unsigned review of the collection was printed in The Literary World on August 17 and August 24 titled "Hawthorne and His Mosses".

Melville wrote that these stories revealed a dark side to Hawthorne, "shrouded in blackness, ten times black". He was composing his novel

Moby-Dick at the time, and dedicated the work in 1851 to Hawthorne: "In token of my admiration for his genius, this book is inscribed to Nathaniel Hawthorne."

In "Hawthorne and His Mosses", Herman Melville wrote a passionate argument for Hawthorne to be among the burgeoning American literary canon, "He is one of the new, and far better generation of your writers."

In this review of Mosses from an Old Manse, Melville describes an affinity for Hawthorne that would only increase: "I feel that this Hawthorne has dropped germinous seeds into my soul. He expands and deepens down, the more I contemplate him; and further, and further, shoots his strong New-England roots into the hot soil of my Southern soul."

ABOUT

NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE

In college Hawthorne had excelled only in composition and had determined to become a writer. Upon graduation, he had written an amateurish novel, Fanshawe, which he published at his own expense—only to decide that it was unworthy of him and to try to destroy all copies. Hawthorne, however, soon found his own voice, style, and subjects, and within five years of his graduation he had published such impressive and distinctive stories as “The Hollow of the Three Hills” and “An Old Woman’s Tale.” By 1832, “My Kinsman, Major Molineux” and “Roger Malvin’s Burial,” two of his greatest tales—and among the finest in the language—had appeared. “Young Goodman Brown,” perhaps the greatest tale of witchcraft ever written, appeared in 1835.

The main character of The Scarlet Letter is Hester Prynne, a young married woman who has borne an illegitimate child while living away from her husband in a village in Puritan New England. The husband, Roger Chillingworth, arrives in New England to find his wife pilloried and made to wear the letter A (meaning adulteress) in scarlet on her dress as a punishment for her illicit affair and for her refusal to reveal the name of the child’s father. Chillingworth becomes obsessed with finding the identity of his wife’s former lover. He learns that Hester’s paramour is a saintly young minister, Arthur Dimmesdale, and Chillingworth then proceeds to revenge himself by mentally tormenting the guilt-stricken young man.

Hester herself is revealed to be a compassionate and splendidly self-reliant heroine who is never truly repentant for the act of adultery committed with the minister; she feels that their act was consecrated by their deep love for each other. In the end Chillingworth is morally degraded by his monomaniac pursuit of revenge, and Dimmesdale is broken by his own sense of guilt and publicly confesses his adultery before dying in Hester’s arms. Only Hester can face the future optimistically, as she plans to ensure the future of her beloved little girl by taking her to Europe.

NOVELS

- Fanshawe (published anonymously, 1828)

- The Scarlet Letter, A Romance (1850)

- The House of the Seven Gables, A Romance (1851)

- The Blithedale Romance (1852)

- The Marble Faun: Or, The Romance of Monte Beni (1860) (as Transformation: Or, The Romance of Monte Beni, UK publication, same year)

- The Dolliver Romance (1863) (unfinished)

- Septimius Felton; or, the Elixir of Life (unfinished, published in the Atlantic Monthly, 1872)

- Doctor Grimshawe's Secret: A Romance (unfinished, with preface and notes by Julian Hawthorne, 1882)

Hawthorne’s high rank among American fiction writers is the result of at least three considerations. First, he was a skillful craftsman with an impressive arthitectonic sense of form. The structure of The Scarlet Letter, for example, is so tightly integrated that no chapter, no paragraph, even, could be omitted without doing violence to the whole. The book’s four characters are inextricably bound together in the tangled web of a life situation that seems to have no solution, and the tightly woven plot has a unity of action that rises slowly but inexorably to the climactic scene of Dimmesdale’s public confession. The same tight construction is found in Hawthorne’s other writings also, especially in the shorter pieces, or “tales.” Hawthorne was also the master of a classic literary style that is remarkable for its directness, its clarity, its firmness, and its sureness of idiom.

A second reason for Hawthorne’s greatness is his moral insight. He inherited the Puritan tradition of moral earnestness, and he was deeply concerned with the concepts of original sin and guilt and the claims of law and conscience. Hawthorne rejected what he saw as the Transcendentalists’ transparent optimism about the potentialities of human nature. Instead he looked more deeply and perhaps more honestly into life, finding in it much suffering and conflict but also finding the redeeming power of love. There is no Romantic escape in his works, but rather a firm and resolute scrutiny of the psychological and moral facts of the human condition.

A third reason for Hawthorne’s eminence is his mastery of allegory and symbolism. His fictional characters’ actions and dilemmas fairly obviously express larger generalizations about the problems of human existence. But with Hawthorne this leads not to unconvincing pasteboard figures with explanatory labels attached but to a sombre, concentrated emotional involvement with his characters that has the power, the gravity, and the inevitability of true tragedy. His use of symbolism in The Scarlet Letter is particularly effective, and the scarlet letter itself takes on a wider significance and application that is out of all proportion to its literal character as a scrap of cloth.

Hawthorne’s work initiated the most durable tradition in American fiction, that of the symbolic romance that assumes the universality of guilt and explores the complexities and ambiguities of man’s choices. His greatest short stories and The Scarlet Letter are marked by a depth of psychological and moral insight seldom equaled by any American writer.

EARLY LIFE

Nathaniel Hawthorne was born on July 4, 1804, in Salem, Massachusetts; his birthplace is preserved and open to the public. William Hathorne was the author's great-great-great-grandfather. He was a Puritan and was the first of the family to emigrate from England, settling in Dorchester, Massachusetts, before moving to Salem. There he became an important member of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and held many political positions, including magistrate and judge, becoming infamous for his harsh sentencing.

William's son and the author's great-great-grandfather John Hathorne was one of the judges who oversaw the Salem witch trials. Hawthorne probably added the "w" to his surname in his early twenties, shortly after graduating from college, in an effort to dissociate himself from his notorious forebears. Hawthorne's father Nathaniel Hathorne Sr. was a sea captain who died in 1808 of yellow fever in Dutch Suriname; he had been a member of the East India Marine Society. After his death, his widow moved with young Nathaniel and two daughters to live with relatives named the Mannings in Salem, where they lived for 10 years. Young Hawthorne was hit on the leg while playing "bat and ball" on November 10, 1813, and he became lame and bedridden for a year, though several physicians could find nothing wrong with him.

In the summer of 1816, the family lived as boarders with farmers before moving to a home recently built specifically for them by Hawthorne's uncles Richard and Robert Manning in Raymond, Maine, near Sebago Lake. Years later, Hawthorne looked back at his time in Maine fondly: "Those were delightful days, for that part of the country was wild then, with only scattered clearings, and nine tenths of it primeval woods." In 1819, he was sent back to Salem for school and soon complained of homesickness and being too far from his mother and sisters. He distributed seven issues of The Spectator to his family in August and September 1820 for the sake of having fun. The homemade newspaper was written by hand and included essays, poems, and news featuring the young author's adolescent humor.

Hawthorne's uncle Robert Manning insisted that the boy attend college, despite Hawthorne's protests. With the financial support of his uncle, Hawthorne was sent to Bowdoin College in 1821, partly because of family connections in the area, and also because of its relatively inexpensive tuition rate. Hawthorne met future president Franklin Pierce on the way to Bowdoin, at the stage stop in Portland, and the two became fast friends. Once at the school, he also met future poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, future congressman Jonathan Cilley, and future naval reformer Horatio Bridge. He graduated with the class of 1825, and later described his college experience to Richard Henry Stoddard:

I was educated (as the phrase is) at Bowdoin College. I was an idle student, negligent of college rules and the Procrustean details of academic life, rather choosing to nurse my own fancies than to dig into Greek roots and be numbered among the learned Thebans.

LATER YEARS

At the outset of the American Civil War, Hawthorne traveled with William D. Ticknor to Washington, D.C., where he met Abraham Lincoln and other notable figures. He wrote about his experiences in the essay "Chiefly About War Matters" in 1862.

Failing health prevented him from completing several more romance novels. Hawthorne was suffering from pain in his stomach and insisted on a recuperative trip with his friend Franklin Pierce, though his neighbor Bronson Alcott was concerned that Hawthorne was too ill. While on a tour of the White Mountains, he died in his sleep on May 19, 1864, in Plymouth, New Hampshire. Pierce sent a telegram to Elizabeth Peabody asking her to inform Mrs. Hawthorne in person. Mrs. Hawthorne was too saddened by the news to handle the funeral arrangements herself. Hawthorne's son Julian was a freshman at Harvard College, and he learned of his father's death the next day; coincidentally, he was initiated into the Delta Kappa Epsilon fraternity on the same day by being blindfolded and placed in a coffin. Longfellow wrote a tribute poem to Hawthorne published in 1866 called "The Bells of

Lynn". Hawthorne was buried on what is now known as "Authors' Ridge" in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Concord, Massachusetts. Pallbearers included Longfellow, Emerson, Alcott, Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., James Thomas Fields, and Edwin Percy Whipple. Emerson wrote of the funeral: "I thought there was a tragic element in the event, that might be more fully rendered—in the painful solitude of the man, which, I suppose, could no longer be endured, & he died of it."

His wife Sophia and daughter Una were originally buried in England. However, in June 2006, they were reinterred in plots adjacent to Hawthorne.

Nathaniel

Hawthorne visited Herman and Elizabeth

Melville at Arrowhead, now a heritage site of some significance, is

now on the National Monuments Register, fully restored.

LINKS

& REFERENCE

https://www.

Herman

Melville married Elizabeth Shaw and eventually moved to Arrowhead, where

Moby Dick was written. They also lived in Lansingburgh, Troy, New

York. It was while at Arrowhead that the Melville's socialized with

the Hawthorne's.

Please use our

A-Z INDEX to

navigate this site