|

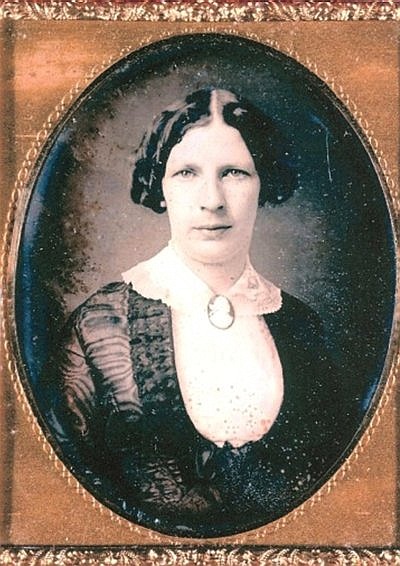

ELIZABETH SHAW

Please use our A-Z INDEX to navigate this site

|

Elizabeth Shaw was the wife of Herman Melville. Apart from raising a family together, Lizzie functioned as an editor and manager of writings while Herman was active creatively. Unsurprisingly, she seems to have lost impetus and sight of the value of the unpublished manuscript: Billy Budd, as did the rest of her family, until the work was discovered in tin 1918. A prophet is rarely recognised in his own land, let alone by his close family.

Elizabeth Shaw was born June 13, 1822 in Boston, Massachusetts. She was the daughter of Elizabeth Knapp Shaw and Lemuel Shaw, Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Court and a long-time friend of the Melville family.

Everyone called

Elizabeth, Lizzie. Her siblings were all boys, John Oakes, Lemuel and Samuel Savage Shaw.

Elizabeth was the first Melvillean. Beyond copying Herman’s work in his life, she maintained his literary reputation after his death. Her labor exhibited itself in the subtlest ways. On the back flyleaf of the Melville family’s copy of The Piazza Tales, someone (likely Elizabeth) wrote the original publication dates of all the stories collected in the book. This book by Herman, annotated by Elizabeth, illustrates the intertwined nature of their shared bibliographic production, and the importance of this shared labor in the reception and study of Herman Melville.

This book shows how Elizabeth’s labor exists in a tradition of note-taking and information management that bibliographic scholars like Ann Blair and Richard Yeo recognize as intellectual work in its own right. Considered within these histories, Elizabeth’s labor is a cumulative practice, in which textual copying establishes an expertise that she draws from to edit later editions of those texts.

While Elizabeth had no monographs, scholarly editions, or novels of her own, her labor made those that would come after her possible, as an editor and confidant.

Herman would tell stories of his adventures to his family and friends. At the urging of his sisters, Melville began to write down his stories. The result was five books all drawing on his experiences at sea.

In the summer of 1845, Melville completed his first novel

Typee, which was based on his adventures on the Marquesas Islands. After some difficulty in finding a publisher, Typee was first published in 1846 in London, where it was very popular. A Boston publisher subsequently accepted

the sequel: Omoo, sight unseen.

The new Mrs. Herman Melville kept her stepmother in Boston informed of her daily life:

As much as Melville loved the Berkshires, he grew frustrated at the lack of success of his writing career and found his debts mounting.

In 1863 Herman traded Arrowhead for his brother Allan’s house at 104 East 26th Street in New York City to offset debt and mortgage payment arrears. Lizzie loathed winters in the country, and Herman needed the stimulation of an active community around him.

Fortune smiled on the Melville's with inheritances from both sides of the family, enabling them to pay off some debts, and they were pleased to return to city life. They lived off Lizzie’s inheritance after the death of her father. Melville continued to visit Arrowhead through the 1880s.

Herman

took a position as a customs inspector on the New York docks in 1866

resulting from family pressure to find gainful employment. He held this job for twenty years, working six days a week with only two weeks of vacation a year. The man who had sailed the world and written great American literature now found himself working at a job that paid four dollars a day.

Nobody

knows if the fatal shooting was intentional or accidental. Their son Stanwix

went to sea in 1869. He died of tuberculosis in a San Francisco hospital in 1886. As for the Melville daughters, one was a spinster, and the other reportedly did not want to hear her father’s name, regarding him as a beast.

In August 1918, Raymond M. Weaver, a professor at Columbia University, doing research for what would become the first biography of Melville, paid a visit to Melville's granddaughter, Eleanor Melville Metcalf, at her South Orange, New Jersey home.

Eleanor gave him access to all the records of Herman Melville that survived in the family: manuscripts, letters, journals, annotated books, photographs, and a variety of other material.

Among these papers, Professor Weaver was astonished to find a substantial manuscript for an unknown prose work entitled Billy Budd.

Please use our A-Z INDEX to navigate this site

|

|

This website is Copyright © 2020 Cleaner Ocean Foundation Ltd and Jameson Hunter Ltd

|