|

ENGLISH HERITAGE

Please use our A-Z INDEX to navigate this site

|

|

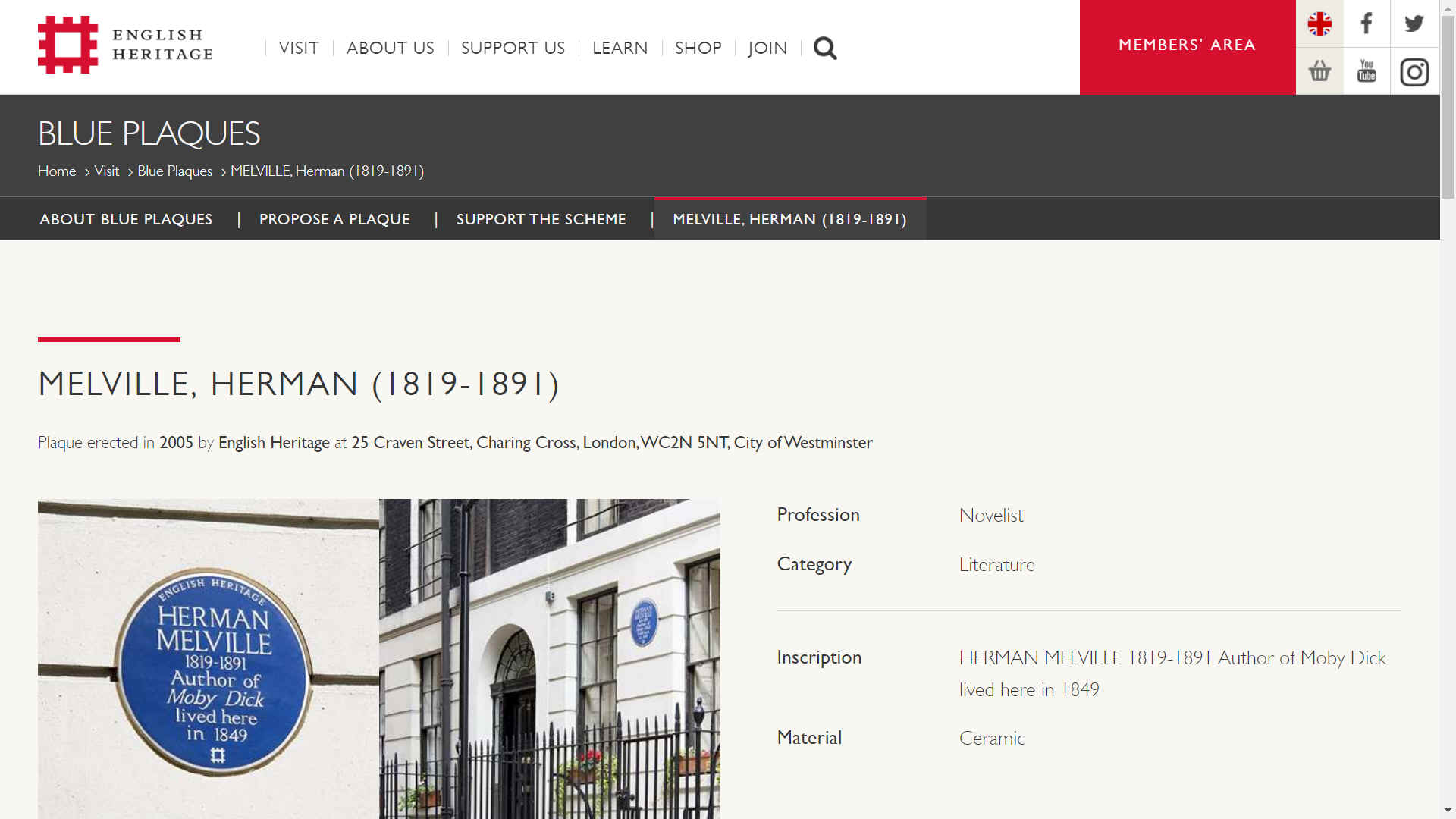

He didn't live at this address for long, but it was time enough for English Heritage to record the stay as part of their Blue Plaque geographical historic reference scheme.

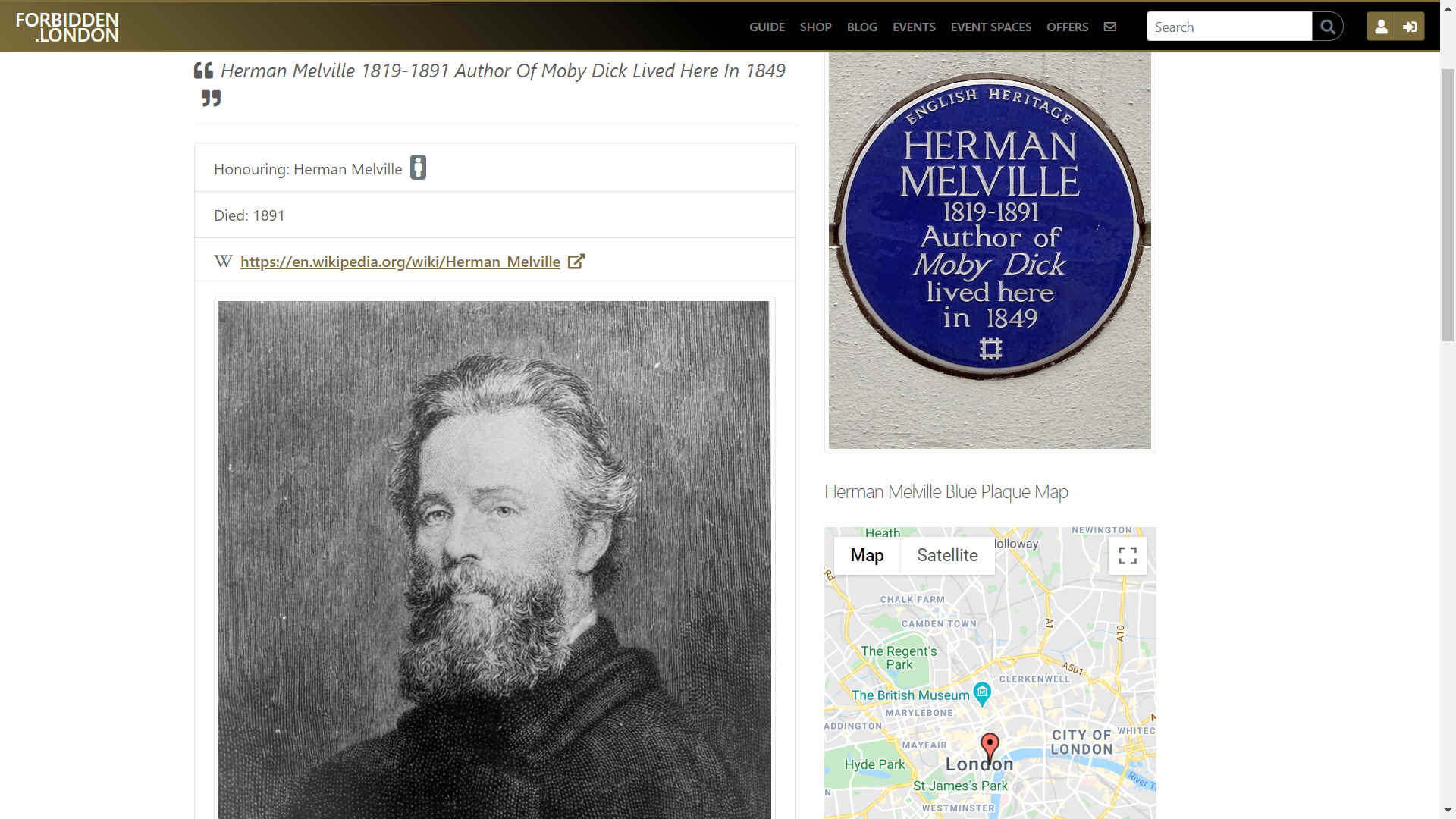

Herman Melville was born in New York City on the 1st of August 1819. He died on the 28th of September 1891. He was an American novelist, short story writer and poet of the American Renaissance period. The centennial of his birth in 1919 was the starting point of a Melville revival, 28 years too late to do Herman any good.

Melville was the author of

Moby

Dick, often described as the definitive American novel. He is commemorated with a blue plaque at 25 Craven Street in Charing Cross, where he stayed for a few weeks at the end of 1849.

In his diary, he recorded seeing the Lord Mayors Show, a public hanging, the British Museum, the National Gallery and London Zoo. So, he really crammed it in.

In 1861, the death penalty in the UK was abolished for all crimes except those of high treason,

piracy with violence, arson in

royal dockyards, and murder. Some seven years later, public hanging ended, with the introduction of the Capital Punishment Act.

The failure of this work and of its satirical successor, Pierre (1852) brought about a mental breakdown from which Melville never entirely recovered. Largely forgotten by literary society, he became a New York customs inspector, and abandoned fiction for poetry, save for a last unfinished novel, Billy Budd (published 1924).

ABOUT ENGLISH HERITAGE

The extraordinary collection of buildings and monuments now in the care of

English Heritage began to be amassed in 1882. At that stage heritage was the responsibility of the Office of Works, the government department responsible for architecture and building. In 1913 an Act of

Parliament was passed that gave the Office new powers. These were essentially to make a collection of all the greatest sites and buildings that told the story of Britain. At that stage these were regarded as being prehistoric and medieval remains - country houses and industrial sites were then not really seen as heritage.

After some debate it was decided that it would be financially more sustainable if the National Trust took on the country houses

like Rudyard

Kipling's Batemans

at Burwash in East Sussex, and that the Ministry of Works confined itself to the older monuments.

The agenda to collect more buildings is a potential conflict of interest when it comes to conservation of buildings they may wish to acquire.

Over a period of a decade or more, the collection became better run, better displayed and the old season ticket was transformed into a membership scheme. Lord Montagu and his successor as chairman, Sir Jocelyn Stevens, began to collect more buildings, now including country houses, such as Brodsworth Hall. Membership grew, visitor numbers increased, and people enjoyed the collections more than ever before. In fact, by the mid-2000s, income from the collection was beginning to make a contribution to their maintenance and conservation. In 2011, for the first time, the national

heritage collection made an operational surplus. In other words, instead of costing money to open it to the public, a small surplus was made.

You will not find them helpful if you have a building of local interest that is not listed. Listing, is a problem for private owners, due to the burdens and restrictions imposed. Perhaps this should be something the UK should look at in terms of slowing the disappearance of lesser know archaeology.

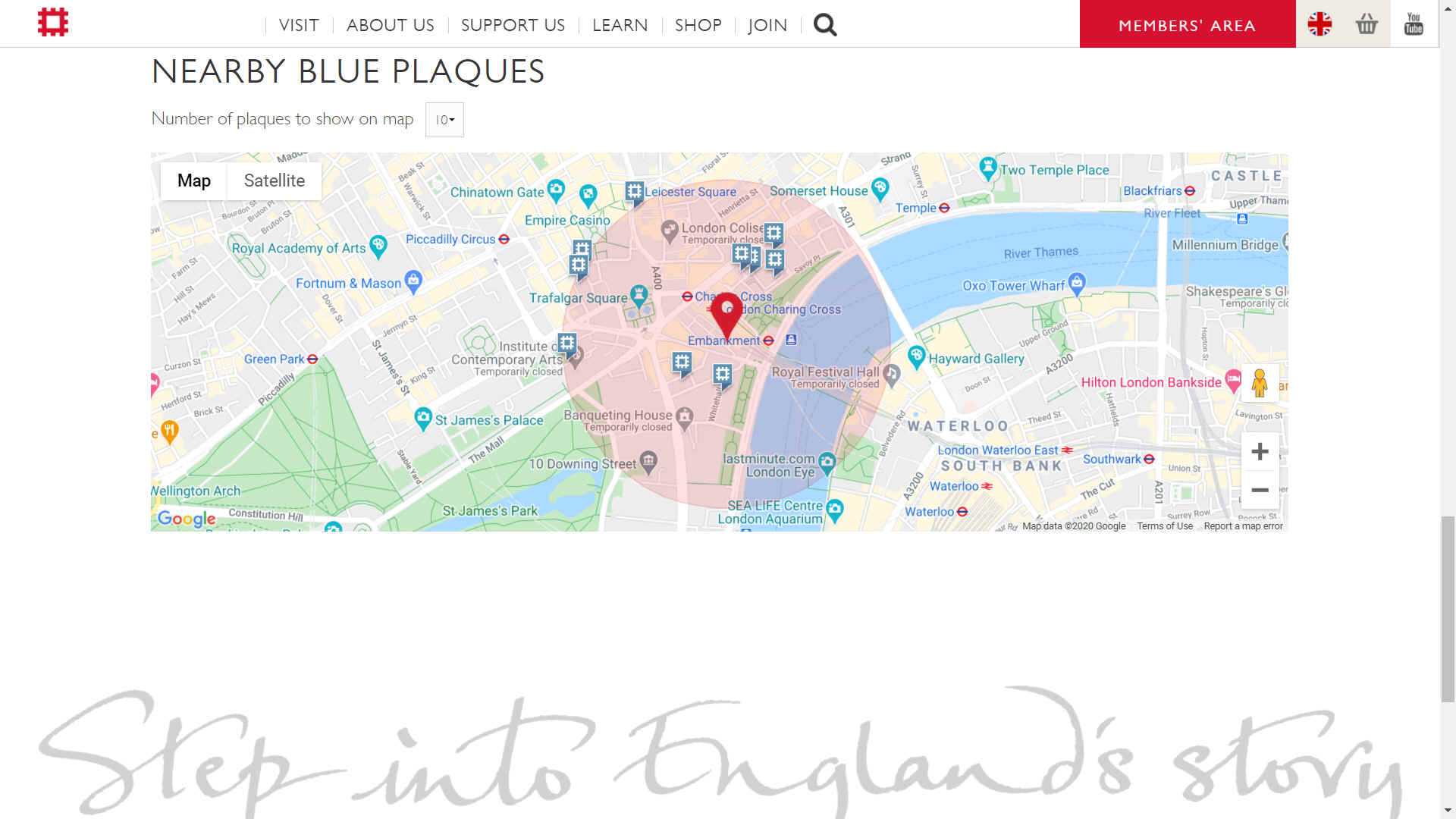

CHARING CROSS - A map showing where Herman Melville lived in 1849. Next time you are in London near the Embankment or River Thames, why not take a detour.

CONTACTS

Telephone: 0370 333 1181 or

English Heritage 6th Floor

U.S. Embassy London

LINKS & REFERENCE

https://forbidden.london/en/blue-plaques/1570 https://uk.usembassy.gov/cultural-connections-london/herman-melville-blue-plaque/ https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/blue-plaques/herman-melville/ https://www.whalingmuseum.org/ https://lansingburghhistoricalsociety.org/ https://www.mobydick.org/ https://melvillesociety.org/ http://melville.org/

Herman Melville was the author of a novel abut what we'd now consider an illegal activity; the commercial hunting of whales for oil and meat. In capturing the whaling industry at its peak, showcasing the rebellious white whale, in our view he was lobbying for the whales, the innocent victims in his story. Following his death in New York City in 1891, he posthumously came to be regarded as one of the great American writers.

Please use our A-Z INDEX to navigate this site

|

|

|

This website is Copyright © 2020 Cleaner Ocean Foundation Ltd and Jameson Hunter Ltd

|